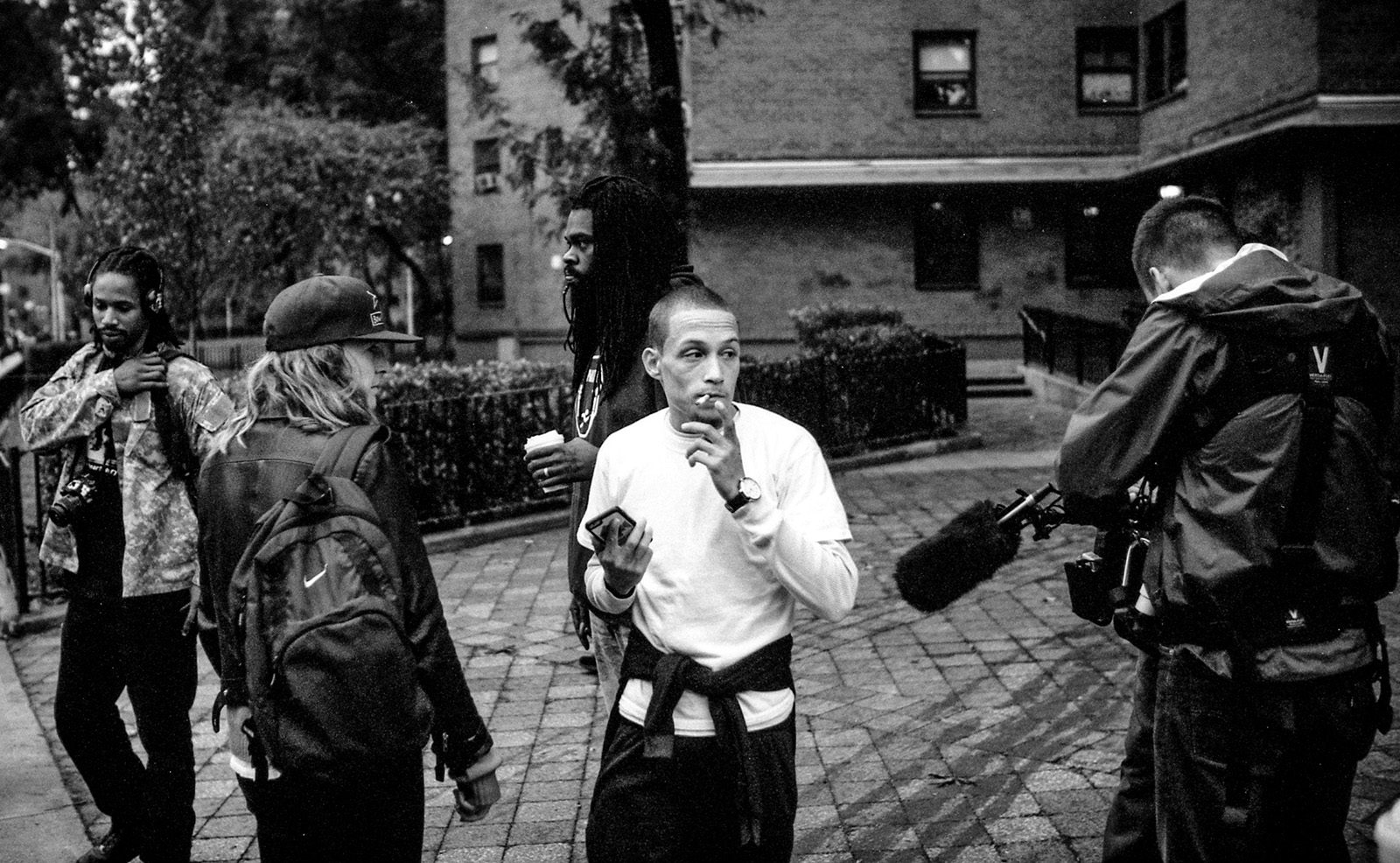

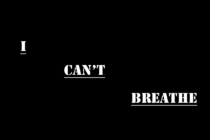

It has been impossible to ignore the flurry of social media videos showing the continued violence perpetrated by law enforcement officers against black bodies in the United States. 2017 was a high point with a police shooting seemingly every day. This tipping point spurned a revamping and ramping up of activism including, now more than ever, providing picture and video evidence as documentation against police brutality. Activists put themselves in harm’s way and often in the cross-hairs of the police doing this. Ramsey Orta, who stood up to the police and filmed the viral footage of Eric Garner’s murder, is the only person serving jail time from that event, and mostly because he exposed the police.

WeCopwatch

CopWatch is a documentary focusing on WeCopwatch – an organisation that film police brutality in a US black community. We caught up with its director Camilla Hall to find out more about this sometimes harrowing and tragic, but ultimately powerful and beautifully-made film.

What made you decide to become involved in this project with such a timely and powerful topic?

I think being British, our relationship with the police in general is quite different to that in America, so while I was living there and saw these videos of police violence, I felt that they were so extraordinary and shocking and unjustifiable. I felt like I had to do something, and I came into contact with WeCopWatch after reading about Ramsey Orta and Kevin Moore in the news. Once I met them, I saw that there was so much to their story and I felt that it was important to tell it. The group was incredibly inspiring and I wanted to create a platform for more people to know about them and see copwatching as a way to help the community.

What did you want to achieve when you made this film? Was it an awareness project or did you want to dig deeper into the psyche of people who had been involved?

The idea of this film was to send a message that you could be a support to someone else just by standing by and filming an incident between somebody and the police. Whoever you are, whatever your race, background, or economic status, you could take a phone, you could film, and you could create a piece of evidence for that person. We can look all look out for each other.

If a police officer is doing nothing wrong then they shouldn’t be disturbed by filming

What would you say to people that suggest that organisations like We CopWatch are inflammatory or trying to make a problem out of something that isn’t there, or targeting the police?

If a police officer is doing nothing wrong then they shouldn’t be disturbed by filming. The only time you’d get nervous would be if you were doing something wrong, like what was clearly happening in the (Eric) Garner video. Cop watching ultimately acts as accountability for police officers. Of course as cop watchers there are ways to not be intrusive. Keep your distance, don’t involve yourself, and don’t engage with the person getting arrested. You’re merely a bystander, but be resolute and stand your ground.

You interest me as you’re a journalist, working for 5 years in the Middle East, and you’re a white British female. How did you use each of these perspectives to help you direct this film?

The gut feeling to do it came out of being a journalist – this was an important story to be told. At first, I tried to find someone else to tell the story, for example a person of color to direct, but the story was moving so fast that in the end, without funds to pay someone else, I had to go ahead with the film myself. The access that I had been granted was also hard to transfer to someone else at that early stage. However, I knew it was important to get a lot of other perspectives on the film as I made it.

In the end, as a white British female, it was easier in a way as I wasn’t judged in an American context. I was clearly an outsider, without predictable preconceptions about anyone or their story. I built up a relationship with the subjects of the documentary. The co-founders Jacob and David, who built the group were incredible guides into the subject and taught us a lot about the whole concept of copwatching. Their passion was clear and I wanted to show that to other people.

I built up a relationship with the subjects of the documentary who trusted and chose to talk to me. I think I was just totally random to be honest.

It was important to me that people of colour worked on the film, gave us feedback and watched the film before it was released. We had a lot of feedback and it felt right for everyone who was affected by it. Interestingly, some people, particularly white people, who have had no experience with police brutality or no loved ones affected by it have been the hardest ones to be convinced about the film. The fight to reach those people is harder than I imagined.

How would you respond to people that say black people should be able to tell their own story? A lot of times black people’s stories are taken away from them, is this not one of them?

I think it’s a very worthy but difficult debate. I think there’s ways to elevate and help people tell their story. As a producer I’m now focused on helping directors of colour, e.g. finding distribution or financing. In this case the story had to be told as it was moving so fast, I was aware of the situation, that I was a white female telling the story, but what was most important to me was that the subjects in the film felt like their stories were being told and that they supported the film. Definitely the current situation where many black people aren’t in a position to tell their own story or finance their films has to change but stopping alternative outlets of storytelling shouldn’t happen either. The answer is for white people to do more to help people of color to get their stories, ideas and films made. Producing other people’s work is the simplest answer.

This was your directorial debut – how did you go about making the film?

It started off with very little money, I just borrowed, asked friends, and tried to get a little funding. It started with myself and Adriel Gonzales, a cinematographer straight out of university. For the first shoot, he and I spent 10 days at the WeCopWatch headquarters in St Louis. I believe it to be one of the most dangerous areas in the US – we were shot at on 2 separate occasions. That first trip, we arrived with two sleeping bags, it was so cold and the house only just had the electricity turned on and no water. I was put through my paces, not only as a director but also cop watching.

How have your perceptions changed since seeing first hand what’s been happening?

I wasn’t aware of the gigantic toll activism takes on a person, but now I’ve seen what they sacrifice and what they’ve gone through to continue to stand up to police brutality.

In general, I believe it’s important to question your own privilege, and what you can do to change things. The white privileged can use their economic and/or political advantage to elevate people’s stories. You can be a witness and protect someone in an arrest. It doesn’t matter whether they’ve committed a crime or not, no one deserves to be mistreated or put in a headlock or chokehold.

In terms of content, what was one moment that stuck with you?

There’s one particularly emblematic scene. Ramsey Orta (who filmed the Eric Garner video) is talking about going into prison, Ichi who’s about 3, is in the background trapping a bug with a lid. It’s intercut with Ramsey’s predicament of feeling trapped in a system that you can’t control, that’s not set up for you and that you’re not a part of. A lot of people remember that scene.

What impact and change would you like to see from this film?

I’d like WeCopWatch to get more support so they can be more financially stable. People can also continue to write to Ramsey Orta in prison. And people shouldn’t consign issues like this into the past, there is an urgency to keep pushing and moving forward. Results aren’t instantaneous but people need to remain committed and keep these people’s names in the forefront and the news. Don’t let people forget what happened.

Have you planned a follow up to this documentary or any new projects?

Yes I’ll be supporting some of the WeCopWatch guys produce content – they’re planning to do some work with the native community leaders in the Dakotas, working with border protectors and people trying to defend the land from the oil pipeline plans. I’m also working on a project called Black Barbie, an idea by an amazing African-American female director called Lagueria Davis. She’s been working on set for years and has directed narrative work. This is her first feature length documentary and will look at the perception of black beauty through her own personal story. She’s teaching me a lot!

Copwatch is available for rental on Amazon.

WeCopwatch is a non-profit community activist organisation. If you’d like to support WeCopwatch, link here.